On The Millennium Prize Problems - P Versus NP

Society if P = NP

This is the first part to my series on the Millennium Prize Problems. These problems were selected by the Clay Mathematics Institute in May 2000, and include many famous names like the Reimann hypothesis, Poincaré conjecture and the most pertinent one, P vs NP. Each problem has a $1 000 000 prize, and a guarantee of fame for all who solve one. Evidently, this grand reward is properly assigned, as all these problems but one have withstood the test of time and the cumulative minds of the world’s smartest. As well, each holds a lot of significance, making the million dollars ever more valuable.

What is it?

Without knowing what the P or the NP means, it is hard to grasp what the problem really is. In simplest terms, P is the set of all decision problems whose fastest algorithm to solve runs in polynomial time. On the other hand, NP is the set of all decision problems whose answer can be checked by an algorithm in polynomial time. The essence of the problem is to know if these two sets are really the same (P = NP), as in each problem in NP also exists in P.

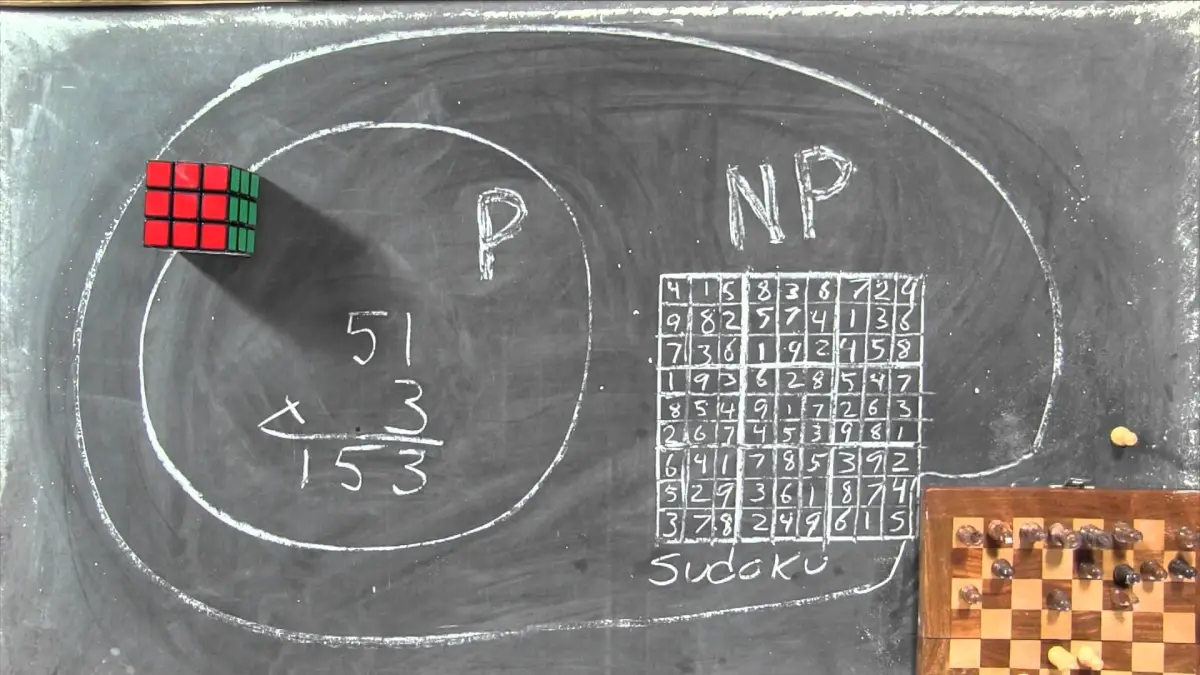

Imagine for a second, a sudoku board filled with numbers. Can you find an algorithm to check if it is correct? This would be relatively simple, because it only requires checking in each row and column and box has all nine numbers distinctly. However, on the flip side, would you be able to find the solution to a partially filled grid easily? Or in a more decision oriented problem, would you be able to determine if there is a solution for any partially filled grid?

This is essentially trying to solve the sudoku board, which you might think is not too bad, since people have been doing that for years. The issue comes when the board grows larger and larger, whereby determining if there is a solution for the board takes more and more time. With a growing board, checking the answer of a sudoku grid becomes harder, but not as hard as solving it. This is a common example of an NP problem.

Okay but what is P

As I stated before, P is the set of all decision problems whose fastest algorithm to solve runs in polynomial time. Let’s break that down.

Decision problems are problems that can be asked as a yes or no problem. This is like our sudoku problem above, we did not ask for what the solved board was, but if there exists a solved board. Another example is determining if a number was prime.

Here, fastest algorithm is relative to a deterministic Turing machine, and how fast it can solve the problem. Turing machines in itself is another large topic. To sum it up, all computational machines can be categorized into different basic models. The Turing machine is the most basic of these, that is capable all the computation that is done in modern day computers, or even human mathematicians.

The deterministic aspect of it makes sure that for a series of inputs, there is ever only one outcome. This is in direct contrast to the non-deterministic Turing machine. The main difference is the ability for randomness in the algorithm.

Finally, let’s look at polynomial time. Time complexity is based on the big-O notation, and is a way to categorize how fast or how slow an algorithm runs. Time is correlated on our real measure of time, but it is also (and more formally) defined as the number of steps taken in an algorithm. It is commonly thought of, for intuition, that a step in an algorithm is equivalent to a loop. A for loop over the integer n would have to take n steps.

The same for loop described above would have a complexity of O(n). This means, as the input, n increases, the time complexity increases at the same rate. This is linear complexity. Another example is the line of code that always loops once and prints “Hello World”. This has complexity of O(1) since it always has the same time complexity no matter what the input n is.

Therefore, the polynomial time basically implies that the time complexity would be only bounded by a polynomial function, like O(n2) or O(n3). This is different from exponential time and all the subsequently larger time complexities like O(2n) or O(22n).

Okay, let’s recap. P is a yes or no question that can be solved by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time.

So NP

NP actually has two definitions, of which I have only provided one. NP is the set of all decision problems whose answer can be checked by an algorithm in polynomial time. I will rephrase that based on what you learned in the previous section. NP is the set of all yes or no questions, whose proofs to that question can be verified by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time. The proof can be the example for the decision problem. For the sudoku problem, the proof is a complete sudoku board.

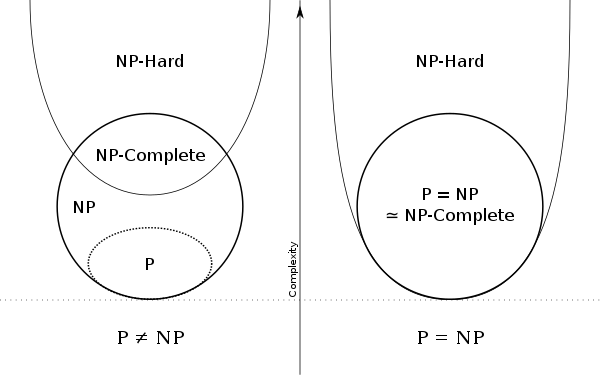

The second definition is the set of all problems that can be solved by a non-deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time. This means that a non-deterministic Turing machine is more powerful than a deterministic one. Importantly, none of our physical computers behave as non-deterministic Turing machines, and therefore it remains as a thought experiment. However, this creates the intuition that P lives within NP, since if a deterministic Turing machine can solve a problem fast, then why can’t a non-deterministic one, especially when the latter is more powerful.

Complexity hardness

An important concept to understand in complexity theory are hard problems, specifically NP-hard problems. A hard problem is a problem that is at least as hard as every other problem in that set. For each NP-hard problem, that problem must be at least harder than every other problem in NP. This means that a problem in NP-hard does not need to be in NP. It could be an impossible problem, but that would still fulfill the requirement that it is at least harder.

A more rigorous definition of hardness is that a problem L is harder than a problem K if the algorithm to solve L can be made to solve K using a transformation taking polynomial time. This assumes that L is already solved.

The set of NP-hard problems is important because of the intersection between the sets NP-hard and NP. This creates the new set, NP-complete problems. Each NP-complete problem is at least as hard as every other NP problem, but with the added requirement that it is also in NP.

A figure showing how the categories of P, NP and NP-hard relate. From wikipedia.

Interestingly enough, there are many problems that exist in this NP-complete set, even the sudoku solving problem that I stated above. The significance of this is that if one of these NP-complete problems are solved with a polynomial time algorithm, then all other NP problems could be solved in polynomial time and P = NP.

The solution

There are many ways to solve this problem. In fact, Gerhard J. Woeginger compiled 62 proofs of this problem that claimed they were true1. Each one has beed refuted.

The first, and most common approach, is to prove that P ≠ NP. However, researchers have figured out that the existing proof methods we have are not capable of creating this proof. Therefore, solving the problem this way requires a new proof technique to be developed, definitely a difficult task.

The second approach, of which two of the 62 proofs tried to use, is to prove that the problem is unprovable, or that it is independent. This faces some issues, whereby all independent problems are unprovable in a certain theory, such as Peano Arithmetic (ie. Goodstein’s theorem and Paris-Harrington theorem). However, this begs the question that if the problem would be able to be proven in a better system. Obviously, we cannot know what we do not know yet, and so a proof of unprovability remains somewhat open-ended.

The third approach is to prove undecidability, of which one proof of the 62 tried to do. Undecidability is not the same as unprovability. Unprovability says that there can never be a proof of the statement, but leaves speculation open for the disprovability, or the proof of the negation. Subsequently, undecidability states that there is no way to ever figure it out. In computation, this means that there is no possible algorithm that will answer the problem even in infinite time.

The fourth approach is where it gets more interesting. This is the proof of the equality between P and NP by the use of a polynomial time algorithm for an NP-hard problem. Many people have done this with problems from many fields of mathematics, however none seemed to have passed the peer review test. Though I could not get solid explanation why, I suspect that each falls for the same issue, that their problems do not satisfy the NP-hardness requirement of transforming their algorithm to one that solves an NP problem in polynomial time.

The fifth and final approach is to prove that there exists a solution for any NP-complete problem in polynomial time. This is different from an actual solution because it does not give an algorithm, but simply says it exists. Theoretically, this could mean that the algorithm is very hard to figure out. The existence of a solution can be proven through equalities of complexity spaces.

Consequence of a solution

The first outcome is that P ≠ NP, which would not change all that much, because a lot of the world’s research already assumes P ≠ NP. In fact a poll from professional mathematicians claimed that 99% of them believe that P ≠ NP.

The second outcome is that we will never know the answer. This practically has the same impact as the first outcome.

The third outcome is that P = NP. This is either proven by an algorithm, or the proof would lead to a lot of research that will eventually develop an algorithm. Either way, the world would change drastically. Cryptography would have to move away from all their traditional systems to a good information-theoretically secure solution. However, on the flip side, many industries would benefit from a solution. For example, operations research would greatly improve because of a solution to the travelling salesman problem. As well, new advances in the life sciences would incur because protein folding is a NP-complete problem.

So find a solution

It surprised me when Wikipedia casually mentioned that there were 62 proposed solutions to the problem. It surprised me even more when I opened Gerhard J. Woeginger’s website and found the updated 116 proposed solutions. Even this website stops at 2016, so there is most definitely more work that is to come on the subject.

I got the impression that this problem was already stale. That it was very widely accepted that P ≠ NP, and the only obstacle was to prove that. It was constantly stated that all the 3000 NP-complete problems have withstood the test of time, and if the smartest people could not solve these, then there probably should be no solution. However, on Gerhard’s website, there were a staggering amount of proofs for their equality. With a simple scroll through, I felt that the amount of attempts at equality have in fact increased as time went on.

This whole journey reminded me of my math camp days. I distinctly remember my teachers telling all the kids about the travelling salesman problem, and how there were a million dollars on the line. I remember me and my friends trying our very best to solve it, only to give up a couple hours later. I could now put myself in the teacher’s shoes, giving an insanely hard problem to a group of promising students, and perhaps holding onto a sliver of a chance that one of them was the next Einstein and would solve it right then and there.

It is interesting that the proof for P = NP is so simple in concept. Solve a sudoku fast, find a path for a traveling salesman fast. These are not theoretically hard to comprehend, but they still stump successive generations of brilliant minds.

We are at the edge of an information revolution as AI advances at an unprecedented rate. Who’s to say that this problem will remain unsolved forever? Maybe the foundation has just been laid to solve the problem, waiting for someone to tie it all together. Maybe that person is you?

Reference

Wikipedia. Practically every bit of information was obtained from the topic’s respective Wikipedia page.

The Wikipedia article is actually out of date, and the website now has 116 proofs of the P versus NP problem. I will still use the numbers found in the Wikipedia page lest I have to count them all. ↩︎